This is a guest post from writer, father, and home cook Herb Durgin.

Corned beef is to St. Patrick’s Day what turkey is to Thanksgiving, or at least what a pillowcase full of candy is to Halloween. Few things speak more to traditional holiday cuisine than that quintessential brisket, boiled—well, simmered—with cabbage and potatoes, carrots and parsnips, and served with a handsome dollop of stone-ground mustard and a pint or four of beer.

Now, to begin with a clear conscience, I feel the need to address a certain elephant in the room: corned beef is not actually an Irish dish; it’s American. The corned-beef-and-cabbage I describe is the Yankee boiled dinner. That it has become symbolic of St. Paddy’s is testament to America’s freedom and prosperity. No, seriously. The nearest the Irish have to the corned beef dinner is bacon-and-cabbage, and while I abide the philosophy that everything’s better with bacon, this dish came about because the beef that the Irish farmers raised, slaughtered, and salted was priced at a luxury affordable only to the British gentry. When the Irish began arriving in America in the 1600s, beef was affordable, so they converted their recipe from a slab of salted pig to a slab of salted cow. And now you know.

In considering corned beef, there are two options: (a) buy a commercially-rendered prepackaged brisket pumped full of chemical preservatives and available for two weeks out of the year, or (b) make one from scratch in one’s own kitchen, to the praise and adulations of everyone around, at any time of year. I’ve never cared much for the bland, slightly tinny taste of the prepackaged stuff, and as a dyed-in-the-wool New Englander I am want to have a boiled dinner more than once a year, so I make my own. The hardest part is planning the meal out at least ten days in advance, which (cue dramatic music) is the exact reason I’m writing this now.

Corning beef begins with the brisket. Other cuts can be used, but brisket is traditional, so it’s what I prefer. In terms of bovine anatomy, the brisket primal covers the deep and superficial pectoral muscles, which for quadrupeds means supporting a significant portion of the carriage weight. This equates to a lot of connective tissue that must be cooked out slowly, but creates a rich and unctuous dish. Flat-cut brisket comes from the deep muscle and is far leaner than the point-cut, which needs to be trimmed of excess fat. Ideally, the cap should be no thicker than a half-inch.

Most recipes call for corning the beef in water-based brine. Normally I’m a big advocate for brining—I brine everything from pork ribs to turkeys—but in the case of corned beef, I prefer dry-curing. This method takes a little longer, but produces a more complex body of flavor. Trust me.

Left to its own devices, a piece of beef cooked for a long period of time turns a grayish color as the heat breaks down the myoglobulin proteins. Since most folks envision the pink of a nice medium-rare steak when they think of beef, they’re turned off by this dull color. To counter that, most commercial producers add sodium nitrate to their corning solutions, which helps the meat maintain an appetizing roseate. Excess nitrates in the diet have also been linked to increased cancer risks, so there’s that. Personally, I’m willing to accept the hoary color, so I leave out the saltpeter.

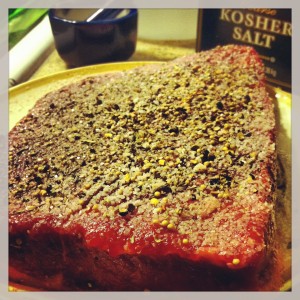

As to what I do use: whole mustard seed, black peppercorns, and coriander seed, along with a few allspice berries, some red chili flake, caraway seed, and a bay leaf. I toss this into my mortar with a bit of salt and tap it to a coarse grind. With this I coat my brisket, favoring the exposed surface but hitting up the fat cap, too. Both sides then get a generous coating of kosher salt. Fun fact: the term “corned” refers to the large grains (or corns) of salt used in the preservation. Since I’m brining the meat in its own liquid, kosher salt is by design perfect, since it sticks to the surface and draws out the moisture better than other varieties.

Once I’ve coated the meat—and taken pictures to which I will add filters and upload to Instagram as #FoodPorn—I place the brisket in a gallon-sized zip-top bag, squeeze out the excess air, seal and date, and drop in the lowest drawer of my refrigerator. Every few days, I’ll turn it over, but other than that I leave it to do its thing. Target curing time is 10-14 days, after which, through the power of osmosis, my seasoned brisket becomes corned beef. (Cooking recipes and such to follow in a few days.)

Follow Herb on Twitter (@HerbDurgin) or #FoodPorn on Instagram (@Katachthonios)